T-Model Ford & GravelRoad(photo via GravelRoad's website)

On April 6, 2012, two different strands of the newest blues movements will be on display in Seattle. Seattle’s own GravelRoad, promoting their excellent progressive/ acid blues album Psychedelta, will be at the Funhouse, and Portland’s Tango Alpha Tango, whom I covered in this forum and who have just released an outstanding new EP, Kill and Haight, will be at Comet Tavern.

This occasion gives me an opportunity to point out the brilliance of GravelRoad– and how they are the heirs of local legend Harry Smith’s best intentions. If you don’t know Harry Smith yet, you will. This Memorial Day Weekend, the recognition of local anthologist Harry Smith continues with a tribute at Seattle’s Northwest Folklife Festival. The Harry Smith concerts, which DJ Greg Vandy and our own Levi Fuller seem to have a large part in putting on, have been building steam. I am more and more impressed with how Mr. Vandy and Fuller have changed the dynamic of a group of songwriters, building collaboration and changing the critical voice, with this focus on classic material.

I’d explain how I feel a lot of us are learning about songwriting by studying the peculiar style of popular folk that Harry Smith tracked down. But that would get dry. Also, I flat out have conflicted feelings about the legendary Anthology of American Folk Music. Having grown up in a house that was part of the folk revival movement– Smith and Lomax dominated our record collection at home, and our library, and my father mocked any musician who played steel strings or, sin of all sins, plugged something in, I have always felt the package of Smith’s Anthology was beautiful but bogus. With the grain and click of those recordings, with the acoustic instruments and yearning vocals, Smith created a complete package that allowed its devotees to infer a rulebook on music and folk art.

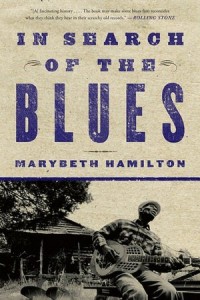

I can’t fully articulate why I cringe over Smith’s masterwork. A recent very well-written book by Marybeth Hamilton, In Search of the Blues, on paperback through Basic Books, explores the history of blues and folk archiving, and the strange tropes that great folk artists since the ’20s have been forced to follow. Hamilton argues that the folk or country blues– the old stuff on the Smith anthology– is really invented by the archivists and not the honest art that the original musicians would have chosen to release or represent themselves. I don’t fully agree with her entire argument, but she approaches my discomfort about the way a great, living music is isolated, stuffed, and taken out of context. (A particularly amusing and truthful moment in the book is when she points out how influential the country singer Jimmy Rodgers was among rural blues singers, to the point where Leadbelly repeatedly wanted to sing Jimmy Rodgers tunes instead of his own.)

I can’t fully articulate why I cringe over Smith’s masterwork. A recent very well-written book by Marybeth Hamilton, In Search of the Blues, on paperback through Basic Books, explores the history of blues and folk archiving, and the strange tropes that great folk artists since the ’20s have been forced to follow. Hamilton argues that the folk or country blues– the old stuff on the Smith anthology– is really invented by the archivists and not the honest art that the original musicians would have chosen to release or represent themselves. I don’t fully agree with her entire argument, but she approaches my discomfort about the way a great, living music is isolated, stuffed, and taken out of context. (A particularly amusing and truthful moment in the book is when she points out how influential the country singer Jimmy Rodgers was among rural blues singers, to the point where Leadbelly repeatedly wanted to sing Jimmy Rodgers tunes instead of his own.)

What I want from folk and blues music is the straightforward emotional connection that this style of music allows, but I want it delivered on the artist’s terms. I want to feel as though the artist is performing the way he or she wants to, with full imagination and integrity. And this is where revivalists usually make my skin crawl. Revivalists often are forced to take a pose, limiting themselves or putting more energy into meeting expectations than into crafting and communicating through song.

When Fat Possum Records came up in the early 1990s, offering bold new takes on recording Northern Mississippi musicians, I was impressed. I loved the idea, but not all the recordings worked. Their Junior Kimbraugh recordings and RL Burnside are among the best in the history of blues. (And track down their Asie Payton CD, it is brilliant.) But one of their most legendary releases, T-Model Ford’s Pee Wee Get Your Gun, felt tack – like the old anthologists, the music ended up having to fit into a story, in this case that T-Model is tough and randy, and the music lost out.

Enter Seattle locals GravelRoad, whom I came upon based on the recommendations of Mr. Greg Vandy. These guys tracked down the above-mentioned T-Model Ford, and seemingly with egos entirely stowed away, offered to help him tour and record albums. The result is absolutely astounding. If you track down the Alive Records releases The Ladies Man and Taledragger, on outstanding electric collection of reworkings of great blues riffs with T-Model freestyling and reinventing on the fly, you hear the complete tradition of the blues cranked out by a 90-year-old bluesman with full integrity and imagination. GravelRoad is the foundation on both releases, the invisible foundation, something like Kazuo Ishiguro’s famous butler– never noticed, but the reason everything works.

Harry Smith tracked down great pop folk recordings from a previous era and released them in a palatable collection that allowed some great music to survive. The collection resulted in an odious byproduct of traditionalists swearing by rules that nobody with a soul would abide by. There have been a few other great anthologists and revivalists. And added to this list, accomplishing something that few other artists have, are Seattle’s own GravelRoad and their work with T-Model Ford. Listen to side two of The Ladies Man, a casual, beautiful jam through an original blues tune that then incorporates the Little Walter tune “My Babe,” and you hear the history of the juke joint. Listen to “How Many More Years” off of Taledragger, and you understand the living imagination of a great folk artist. This is something that has continuously astounded me since I bought these records two years ago. I know it has impressed others: at a New Year’s party, I played these records for half the night, and one of the people at the party eventually started a label so he could sign GravelRoad up.

Taledragger blew me away when I heard it. GravelRoad is covering new ground in a genre you might think has been around the block too many times, but these guys really surprised me. Psychedelta is one of the best sounding albums in my collection. Call it acid blues, call it whatever, it’s just one of those records that you can go back to again and again.